Top-down FinOps: why leadership sets the frame

Top-down FinOps aligns cloud economics with leadership intent. It connects technical decisions to margin, risk and runway, turning cloud from a collection of local choices into a strategic lever. Clear boundaries, better language and smart representation make the work matter.

Why top-down FinOps matters now

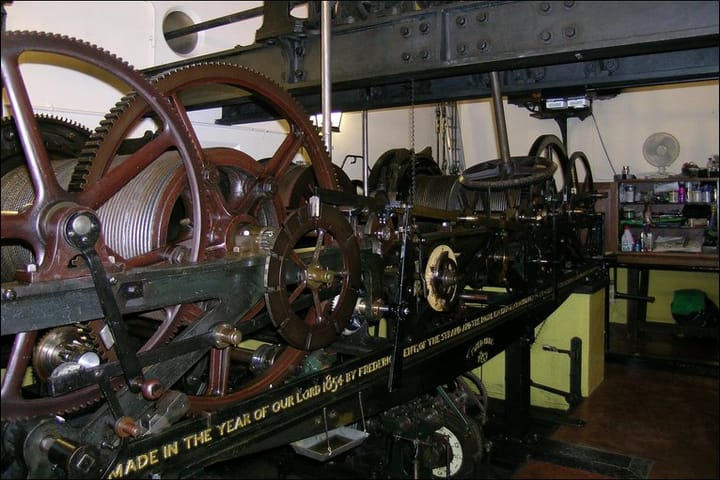

Most FinOps conversations start in the weeds. tags, dashboards, rightsizing, anomalies. The comforting machinery of the bottom-up world.

Useful, yes. Strategic, no.

Cloud has reached a size where its financial impact can no longer be delegated to spreadsheets or well-meaning automation. Spend has crept into the conversations that keep executives awake: margin, runway and the cost of building the future. Add AI to the mix and cloud becomes the closest thing technology has to a living organism—it grows when it wants, eats what it wants and leaves Finance to clean up after it.

If cloud is going to stay in that league, FinOps must rise with it. Not by demanding a seat in the boardroom, that would be unhelpful for everyone involved, but by understanding how leadership works, how decisions cascade and how economic signals travel from the top of the organisation into the architecture that spends the money.

This article is about that cascade: what executives do, what they need and what they never see, why FinOps remains invisible upstairs and why that invisibility matters, and why the real power of FinOps sits not in tooling or tricks but in something far simpler, cloud savings flow straight into profit just like procurement.

Top-down FinOps is not a rebrand or a maturity level; it is a shift in perspective. From policing spend to shaping outcomes, from reporting variance to interpreting intent, from asking how we save money this month to asking what the organisation is trying to achieve and how we help it get there.

If FinOps is going to have influence, it must follow the same path as cloud itself: upward, not outward.

1. What top-down really means

Top-down is one of those phrases that collects unhelpful meanings. People hear it and imagine command-and-control thinking, slow committees or executives hovering over architecture diagrams. None of this is what top-down means in practice.

Top-down is about intent. Not instructions, not micromanagement, intent. It answers one question before any technical work begins: what are we trying to achieve and why does it matter?

Most organisations run cloud in a bottom-up way. Not by design but by history. Cloud entered companies through side doors: shadow IT, early experiments, teams paying with credit cards because it was quicker than raising a purchase order. Cloud vendors encouraged this pattern. They still market primarily to technologists because technologists complain least about procurement and price negotiations—they complain about the platform, not the invoice. For vendors, procurement introduces friction and people who ask unwanted financial questions, so selling to engineers sustains the bottom-up culture.

The result is an architecture shaped by convenience rather than intent. Teams choose services, build features and optimise locally. They do good work, often great work, but the sum of local decisions rarely creates a coherent economic outcome. Cloud spend becomes an accident of delivery rather than an expression of strategy.

Top-down FinOps reverses that pattern. It starts with the strategic direction set by the executive layer—the part of the organisation that decides where to focus, where not to focus and which risks the business is willing to carry. That direction shapes the decisions made by senior technical leaders, decisions such as which platforms to invest in and which to consolidate, how much variance the business can tolerate and where constraints are necessary.

Those constraints define a perimeter. Inside that perimeter teams have more freedom, not less. Clear boundaries remove the political work, the permission-seeking and the fear of stepping on someone else’s budget. A well-shaped perimeter creates a playground where developers can innovate without guessing whether they are about to trigger an unexpected bill or a cross-functional argument. Within that space teams can choose tools, design patterns and approaches that suit their work, knowing that the broader economic direction is already agreed.

Constraints are not a burden. They are one of the most reliable ways to spark innovation. Give people an unrestricted canvas and they wander. Give them a defined problem with clear limits and they invent. Direction empowers; it does not diminish. Good constraints force sharper thinking, cleaner design and more deliberate optimisation. They also give engineers something essential: a shared understanding of what matters and what does not.

This clarity helps engineering push back when the pressure for new features grows beyond what the system can handle. Instead of silent exhaustion or quiet over-spending, the team can point to the agreed perimeter and the trade-offs inside it. The conversation becomes healthier because the ground rules are already set.

Only after this work is done does engineering touch the keyboard. Patterns, guardrails, automation and lifecycle rules become the practical expression of that intent. Costs fall but, more importantly, costs fall in the right places.

Top-down does not suppress autonomy. It creates clarity, and clarity allows teams to act without guessing what matters. In cloud, guessing is expensive. Alignment is cheaper.

This is the foundation on which everything else in the article sits, the idea that cloud economics is not a technical problem but a strategic one, and that FinOps becomes powerful only when it connects to the intent that starts at the top.

2. Why leadership must be involved

Cloud is now large enough to matter. For many organisations it has become one of the biggest operating expenses, one that grows faster than revenue and one that behaves with a mind of its own. When a cost behaves like that it stops being a technical concern and becomes a strategic one.

This is why leadership must be involved. Not to choose services or review dashboards but to set the conditions in which cloud decisions make sense. Executives carry responsibilities that engineering cannot carry, responsibilities such as protecting runway, managing risk, balancing growth against margin and meeting the expectations of shareholders. In a startup those shareholders are often the same people doing the work, which makes the Why uncomfortably real.

Teams will always optimise what they can see. They will fix what is in front of them, remove friction where they feel it and pick the fastest path to delivery. This is natural and often efficient. Yet the sum of those choices rarely adds up to a coherent whole. Without leadership direction cloud spend becomes the cumulative result of well-meaning local decisions rather than an expression of strategy.

AI has pushed this further. No one fully understands its cost behaviour. It is early, volatile and poorly forecasted. The patterns that help with traditional cloud planning do not exist for AI yet, which means variance grows, expectations drift and the conversation between engineering and finance becomes harder.

Leadership involvement is not a luxury. It is the mechanism that makes cloud spend predictable and purposeful. When executives define what matters engineering knows where to invest its time and where to draw the line. Without that clarity teams guess, and guessing is a poor way to manage a budget, especially when the stakes touch margins and runway.

FinOps cannot fill this gap on its own. It can measure, interpret and highlight patterns but it cannot decide which risks are acceptable or which trade-offs support the organisation’s direction. Only leadership can do that. And until leadership makes those choices the organisation will continue to treat cloud as a technical problem rather than what it has become, a strategic lever with financial consequences.

3. What executives actually do

Executives are often described through the wrong lens. People imagine them as decision machines or gatekeepers. In reality their work is simpler and heavier: they define intent, they set boundaries and they carry the risks that others cannot carry.

The best way to understand this is through the Why–What–How model.

3.1 The Why: the executive layer

The Why sits with the CEO, the CFO and, in many organisations, the board. This layer defines direction and protects the organisation from avoidable risk. It decides where the company is going, what it is willing to trade and what it will not compromise. It carries the responsibility to shareholders; in a startup those shareholders may be the same people writing the code, which makes the Why uncomfortably real.

There is also a bias we rarely acknowledge. Most of the FinOps world sees cloud through the filter of LinkedIn success stories, cloud-vendor case studies and startup narratives. These stories come from small, nimble teams that can change direction quickly. They are compelling but they are not the norm. A retail bank, a telecoms provider or a global manufacturer does not want to behave like the sum of a thousand startups. It needs coherence and predictability at scale. Innovation matters, of course, but only in the parts of the business where innovation is useful. Some areas thrive on creativity; others must remain stable because customers expect the world to work the same way tomorrow as it did today.

This is why the Why layer exists. It prevents an organisation from drifting into a collection of local experiments, each one sensible on its own and costly in aggregate. It sets the direction that allows the rest of the structure to work.

This layer does not try to choose technologies. It sets intent, not instructions.

3.2 The What: the strategic design layer

The What belongs to the CTO, the CIO and the senior technical leaders who translate intent into direction. This is the layer that defines the shape of the system, the trade-offs the organisation will accept and the constraints that guide engineering.

The What answers questions such as:

- What platforms we standardise on.

- What we consolidate or retire.

- What risks we take and which ones we refuse.

- What good looks like in performance and in cost.

- What metrics will prove success.

- What boundaries engineering must work within.

The What turns intent into boundaries. It also removes boundaries when the organisation needs space to explore. We see this with AI. In some companies the boundary is set so far away that it feels infinite, a deliberate signal that experimentation should not be slowed. That freedom can be useful, but it creates a different responsibility. When boundaries vanish FinOps must ask for new ones, not to limit innovation but to protect the company from its own enthusiasm. Every experiment has a cost. Every cost has a trade-off. Without boundaries the organisation can wander into risk without noticing.

This is also where FinOps needs representation. FinOps does not decide direction but it interprets the economic consequences of the choices on the table. It becomes the voice that says: if we choose this path, this is the financial shape we should expect.

3.3 The How: the implementation layer

The How sits with architecture, platform teams and delivery teams. This is where intent becomes design and where design becomes action. The How answers the questions that matter day to day: how to build services, how to automate, how to scale, how to make trade-offs inside the agreed boundaries.

The How produces the things we can point at:

- patterns and templates

- automation and guardrails

- lifecycle rules

- performance budgets

- cost-aware design choices

- the daily engineering decisions that move spend up or down

The How is where money flows. It is also where mistakes accumulate when the Why and the What are unclear.

Executives do not need cloud dashboards. They need clarity. They need to know that the Why is shaping the What, and that the What is shaping the How, so that money is being spent in a way that supports the organisation’s direction, not in a way that reflects convenience or habit.

This is the structure FinOps must align with. It is also the structure that makes top-down FinOps work.

4. Why FinOps needs a proxy at the table, not a seat

FinOps often talks about wanting a seat at the executive table. It is an understandable ambition. When you spend your days uncovering waste, correcting behaviour and protecting budgets, you start to believe the work deserves direct access to the people who carry the final responsibility.

The problem is that FinOps is not an executive function. It is not meant to choose strategic direction. It does not decide risk appetite or capital allocation. It cannot speak for shareholders. The work is important but it is not the work of the board.

What FinOps needs is not a seat but a proxy, someone who already sits close to the strategic design layer and who can carry the economic implications of technical choices upward. In most companies that proxy is the CTO or the CIO, sometimes the chief architect, occasionally the CFO. These people already participate in the Why and What discussions and already translate intent into constraints.

FinOps influences through evidence. It shows the economic side of architectural decisions, the financial shape of platform choices and the long-term effects of design patterns. It does not tell executives what to do; it explains what their choices will cost, what they will save and what they will constrain. That is a different kind of power. It is quieter and more durable.

A direct seat would create the wrong expectations. FinOps would be expected to set direction, approve investment or define priorities. None of this is appropriate. FinOps works best when it supports the people who make those decisions, not when it tries to join them.

Representation solves this. With a strong proxy the economic signals from FinOps reach the executive layer without creating a new layer of politics. The proxy understands the trade-offs and can argue for them in the language that executives use: runway, margin, risk, predictability. It allows FinOps to influence the What without pretending to be part of the Why.

This is how FinOps scales. Not by climbing the hierarchy but by aligning with it, not by sitting at the table but by shaping the conversation that takes place there.

5. What executives actually see when FinOps speaks

FinOps produces a great deal of information. It measures waste, highlights anomalies, improves efficiency and explains the financial consequences of technical decisions. The problem is that most of this information is invisible at the executive layer. Not because executives do not care, but because they are looking at a different set of signals.

Executives do not see commitment plans, utilisation graphs or tagging completeness. They do not care whether a cluster is running at sixty per cent or seventy per cent. These details matter to the engineering teams who operate the systems, not to the people who decide the direction of the business.

Executives see margin. They see operating expenses and variance. They see runway and risk concentration. They see anything that affects the financial shape of the organisation. When FinOps speaks in technical categories it fails to connect with the questions executives hold in their hands.

This does not mean executives are disinterested. It means the information must be translated. A cluster running under-utilised is not a cluster problem; it is money leaving the organisation faster than intended. A missing tag is not an operational irritation; it is a blind spot in cost allocation that reduces financial predictability. A poorly configured service is not a technical flaw; it is a margin leak.

FinOps has to speak in these terms. Not to simplify the work, but to make the work visible to the people who can act on it. When savings reduce operating expenses they often improve operating profit. When they do not hit the profit and loss directly they still improve efficiency, reduce waste or free capacity for higher-value work. In every case they improve predictability, which is one of the signals executives trust most.

When FinOps reports only the mechanics it hides its own value. When it reports outcomes it becomes a strategic partner. The work does not change, but the impact does. The moment executives understand that FinOps shapes the economic behaviour of the organisation, the conversation shifts from reporting to influence.

6. FinOps as procurement: the financial power of cloud economics

Procurement has always held a quiet form of power. When it negotiates a better price, the effect is immediate. A lower cost of goods sold improves gross profit. A reduction in operating expenses improves operating profit. There are few places in a business where a one-pound saving produces a one-pound improvement in profit.

Cloud spend sits close to this territory. Much of it appears in operating expenses, sometimes in the cost of goods sold when the product depends directly on cloud usage. When FinOps reduces spend in these categories the effect is often felt directly in the financial statements. Not always, and not automatically, but often enough that it changes the way executives think about the work.

This is why the comparison with procurement matters. FinOps influences the shape, scale and predictability of one of the organisation’s largest costs. It is not an abstract improvement. It is money that would otherwise leave the business. Even when savings do not land on the profit and loss statement—because the spend moves, or is reallocated, or because the accounting treatment changes—they still create value by reducing waste, improving utilisation or freeing capacity for higher-value work.

Executives trust this kind of value. They understand it intuitively because it behaves like established financial levers. Revenue requires sales effort and market demand. Efficiency improvements are sometimes hard to prove. Innovation may or may not pay off. But cost that is no longer incurred is simple. It is clean. It is measurable. It requires no further validation.

FinOps does not need to claim more than this. It does not need to promise transformation or magic. The economic reality is powerful enough. Cloud savings reduce the cost base. Reduced cost increases financial resilience. Financial resilience gives the organisation more freedom to invest, to experiment or to survive a difficult quarter.

This is the heart of the argument. FinOps is valuable because it manages one of the few levers that executives cannot ignore, a lever that ties technical decisions to financial outcomes in a direct and comprehensible way. The work may be technical, but the impact is not.

7. The messy part: what counts as P&L savings, and what does not

Savings sound simple until you try to put them in front of Finance. FinOps teams often find themselves in the same conversation: which improvements will appear in the financial statements and which ones will not. The question looks straightforward yet it rarely is, especially in larger organisations.

Most companies split savings into two broad groups. One group contains reductions that are visible year over year and therefore recognised in the profit and loss statement. The other group contains improvements that prevent spend, delay it or change its shape. These improvements are still valuable, but they do not behave like traditional savings and they do not always appear in the accounts.

This is also why the distinction matters. Savings that flow into financial statements tend to carry more weight with executives. They influence the reported performance of the company. They affect margin and, in some cases, runway. They also influence how external stakeholders see the business. Value exists outside the accounts, but the value that appears inside them is easier for leadership to act on because it is part of the official record.

The difficulty is that classification varies. It varies by company, by industry and by country. It varies with internal policy and with the expectations of auditors. What qualifies as a recognised saving in one organisation may be treated as cost avoidance in another. The bigger the company, and the more regulated it is, the tighter the rules become. These rules are shaped by legislation, accounting standards and the organisation’s own reporting practices.

None of this is unique to one team. Many FinOps practitioners describe the same tension. Some argue that net new commitments should count as recognised savings because they improve the rate from this point forward. Others take the opposite position because the underlying resources did not exist in the previous year. Both views make sense, depending on how the organisation interprets its own policies.

This is why the partnership with Finance is essential. FinOps does not need to resolve the accounting issues. It needs to present the facts clearly and work with Finance to determine how those facts will be treated. The aim is not to push everything into the profit and loss statement. The aim is to understand which improvements have financial reporting consequences and which ones do not, and to describe both categories with the same precision.

A simple principle holds the discussion together. If a change prevents money leaving the organisation it has value. Sometimes that value is recorded in the accounts, sometimes it stays within operational reporting. FinOps cannot control where it lands, but it can control the clarity of the evidence and the quality of the explanation.

When FinOps demonstrates where its work affects the financial statements, even indirectly, the conversation with senior leaders changes. The work becomes part of the financial narrative of the company. It becomes visible at the level where strategy is set.

8. Reading quarterly reports as signals

Quarterly reports look dry from a distance. They read like polished summaries written for investors and analysts, people who live in a world of ratios and expectations. Yet for FinOps they are one of the most reliable sources of executive intent. They show what matters to the company at the level where strategy is made.

The reason is simple. A quarterly report is not marketing material. It is a legal document that represents what the leadership team is willing to be judged on. It contains the priorities they want to emphasise, the risks they want to acknowledge and the direction they want to reinforce. It is the closest thing we have to an unfiltered view of the Why layer.

The language is often broad. It talks about focus, discipline, efficiency and growth. It talks about platform investments, simplification efforts and strategic themes such as AI. These words may seem generic but they carry weight. When a CEO describes a quarter as one of disciplined investment the organisation is being told to take efficiency seriously. When they talk about strengthening the platform they are telling the technical organisation to consolidate, automate and remove drift. When they talk about accelerating AI they are signalling a higher tolerance for spend, but also a higher expectation for clarity.

FinOps does not need to analyse these reports in financial depth. It needs to listen for the patterns. A shift in margin expectations means a shift in how cost is perceived. A focus on predictability means the appetite for variance has changed. A theme around customer experience may indicate where investment should be protected even if spend increases. These signals shape the environment in which cloud decisions are made.

Large companies publish these signals because they must. Smaller companies do it informally through leadership meetings or investor updates. The scale may differ but the intent is the same. Executives tell the world what they are trying to achieve. FinOps becomes more effective when it reads these signals and uses them to frame its own work.

This approach prevents a common mistake. Many FinOps teams present optimisation as a technical exercise. They talk about workloads, patterns and unit costs without connecting their work to the priorities that leaders have already declared. The message becomes easier to ignore because it does not align with the direction of travel.

Reading quarterly reports corrects this. It gives FinOps the language of the Why layer. It helps translate technical insights into strategic consequences. It turns a rightsizing opportunity into a margin improvement or a variance reduction. It turns platform simplification into a response to a declared need for focus. When the work is described in these terms it becomes easier for leaders to act on it.

FinOps does not need to predict the market or read charts. It needs to understand what the company has already committed to. Quarterly reports provide that clarity. They show the trajectory. They reveal the constraints. They make the work of FinOps more relevant because they anchor it in the story the organisation is already telling about itself.

9. Bringing it together: the Why–What–How cascade

Once you see the structure, it becomes difficult to unsee it. Every organisation, whether it admits it or not, follows some version of the Why–What–How cascade. The Why sets direction, the What turns direction into design and the How turns design into practice. Most of the problems we see in cloud economics come from mixing these layers or leaving one of them undefined.

The Why belongs to the executive layer. It determines outcomes, priorities and risk appetite. It describes what the organisation must achieve and what it must avoid. It shapes how the business will be judged, internally and externally. It does not choose technologies. It chooses the context in which technologies will be chosen.

The What sits with the strategic design layer, usually the CTO, the CIO or the senior architecture group. The What turns intent into boundaries. It also removes boundaries when the organisation needs space to explore. We see this with AI. In some companies the boundary is set so far away that it feels infinite, a deliberate signal that experimentation should not be slowed. That freedom can be useful, but it creates a different responsibility. When boundaries vanish FinOps must ask for new ones, not to limit innovation but to protect the company from its own enthusiasm. Every experiment has a cost. Every cost has a trade-off. Without boundaries the organisation can wander into risk without noticing.

The How lives with engineering. This is where intent becomes architecture and where architecture becomes spend. Most of the money flows at this layer, which is why the quality of the Why and the What matters so much. Without them engineering is forced to interpret strategy on its own and the result is rarely coherent.

FinOps spans these layers. It works in the How, where it sees waste, variance and economic drift. It influences the What through the evidence it provides about cost, predictability and long-term consequences. It reflects the Why by translating executive intent into economic implications. When these connections work well the organisation spends money in ways that support its direction rather than dilute it.

This is the essence of top-down FinOps. It is not about control. It is about alignment. It ensures that cloud economics follow the same path as the strategy itself, moving from intent to design to practice. When these layers reinforce one another the cloud becomes a lever rather than a liability. When they do not the cloud becomes a collection of local decisions with global consequences.

The cascade does not solve every problem. It does, however, give the organisation a shape that makes decisions easier and outcomes clearer. And FinOps becomes more powerful when it recognises how its work fits inside that shape and when it is willing to ask for boundaries whenever the absence of them threatens the business.

10. What changes tomorrow

Top-down FinOps is not a new process or a new role. It is a change in posture. It asks the organisation to treat cloud as a strategic lever rather than a technical expense, and to align the economic behaviour of the system with the intent of the people who set that direction.

The change begins with language. FinOps has to speak in outcomes, not mechanics. It has to connect its work to the priorities already set by leadership. When the business talks about margin, FinOps talks about the cost base. When the business talks about runway, FinOps talks about variance and predictability. When the business talks about focus, FinOps talks about the boundaries that shape responsible innovation.

The next step is representation. FinOps does not need a seat at the executive table. It needs a proxy who already participates in the Why and What discussions. That proxy carries the economic implications of architectural choices upward and brings strategic intent back down in a form engineering can act on. Without this connection the work stays small and the decisions stay local.

FinOps also needs to ask for boundaries when the absence of them creates risk. AI is the current example. Some organisations have moved the boundary so far outward that experimentation feels limitless. This can be healthy, but only when the trade-offs are understood. If no boundary exists, FinOps should ask for one. Constraints protect the organisation and sharpen its thinking.

And finally, FinOps needs to pay attention to where its work affects financial reporting. Not because everything must appear on the profit and loss statement, but because the improvements that do appear there carry more weight with senior leaders. Understanding this distinction, and explaining it clearly, brings the work into the conversations that matter most.

None of these changes require permission. They require awareness and a willingness to step into the shape of the organisation rather than work around it. Top-down FinOps aligns intent, design and execution. When these layers reinforce one another the cloud becomes predictable, innovation becomes safer and engineering can move without guessing what matters.

The rest follows from that.

Comments ()